The Systemic Impact of Uncontrolled Gout Beyond Flares and Tophi

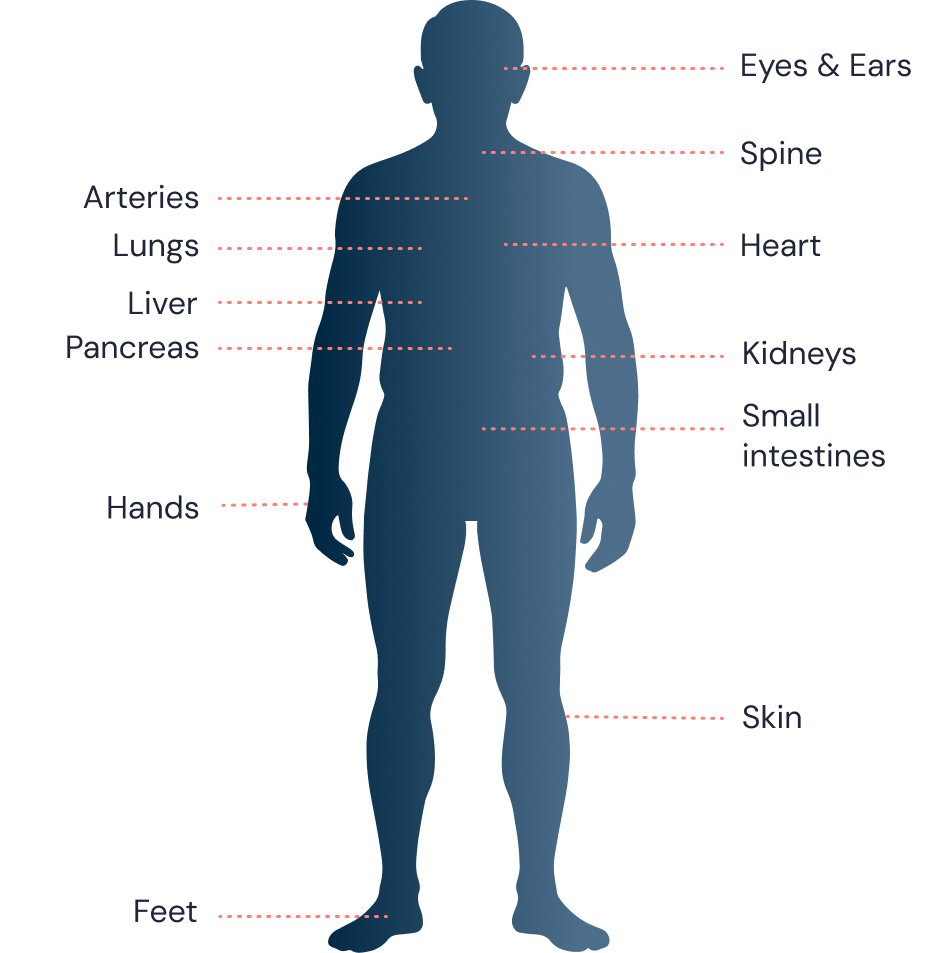

Uncontrolled gout leads to deposits of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals throughout the body, including the heart, kidneys, joints, eyes, and spine. Persistently high sUA levels (>6 mg/dL) despite treatment and having 2 or more recurrent flares a year or visible, non-resolving tophi is a sign that the disease has progressed to uncontrolled gout. This can cause long-term joint and organ damage and potentially negatively impacting overall health.1,3-5

MSU Deposition Throughout the Body3-8

Common Comorbidities With Uncontrolled Gout

Patients with uncontrolled gout may also experience these comorbidities, with their prevalence increasing with higher sUA levels. Common comorbidities include1,5,9:

Diabetes

Cardiovascular (CV) disease

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

Intervertebral degeneration

Metabolic syndrome

Obesity

In 1 study, all patients with urate crystal-confirmed gout had at least 1 comorbidity, and

>95% had 2 or more comorbidities.10*

*The New York Department of Veterans Affairs electronic medical records were examined to allow an assessment of contraindications and comorbidities in patients with gout. Patients were required to have had a clinic or hospital visit during the review period (July 2007 to December 2008), and enrolled patients were identified based on any ICD-9 code for gout (Cohort I; n=575). Cohort II (n=478) was composed of patients in Cohort I meeting the American College of Rheumatology criteria for gout. Cohort III (n=41) was composed of patients in Cohort II with documented monosodium urate crystals in their synovial fluid or tophi. Comorbidities were identified by the presence of physician-assigned ICD-9-CM codes and confirmed by chart review.10

There is a bidirectionality between gout and some of its comorbidities, reflecting uncontrolled gout's systemic nature. The cycle and progression that patients with uncontrolled gout face may worsen comorbidities such as diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and CKD, while some comorbidities may contribute to sustained elevated sUA levels.1,9

In one claims database study, adult patients with uncontrolled gout had an increased risk of1†‡:

Cardiovascular Disease

Patients with uncontrolled gout were 52% more likely to develop heart disease than those with controlled gout

Chronic Kidney Disease

Patients with uncontrolled gout were twice as likely to develop chronic kidney disease than those with controlled gout

Type 2 Diabetes

Gout is an independent risk factor for developing type 2 diabetes

†Patients with controlled gout were defined as having sUA <6.0 mg/dL and patients with uncontrolled gout with sUA ≥8.0 mg/dL.1

‡Data from adult patients with gout and who had at least 90 days of continuous ULT was collected from the Humana Research Database from 2007–2016. A total of 6831 patients were identified that met the inclusion criteria (5473 patients had controlled gout, and 1358 patients had uncontrolled gout).1

Mortality Risks in Uncontrolled Gout

Gout can be associated with a higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease, renal disease, infections, and diseases of the digestive system.1,13,14§

With every 1 mg/dL increase in sUA levels15||:

Coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality increased by

20%

§Based on survival analysis on clinical and radiographic measures of disease severity and mortality in a specialty clinic-based cohort of 706 patients diagnosed with gout by a gout specialist (1992-2008). Mean follow-up was 47 months. Standardized mortality ratios (SMR) were calculated to assess the magnitude of excess mortality among patients with gout compared with the underlying general population.13

||Meta-analysis data from a comprehensive literature search (N=14) in PubMed and Embase for relevant prospective cohort studies assessing the association between hyperuricemia and CHD mortality.15

Uncontrolled Gout Impacts Everyday Life

The debilitating effects of uncontrolled gout go beyond the painful flares and impairment of joint and limb function. When serum uric acid levels remain elevated, disruptions can affect a patient's life and social health, with reduced work productivity and loss of mobility and independence.3,6

Flares in Patients With Uncontrolled Gout Impact Work Productivity and Social Activities16:

Among patients with uncontrolled gout reporting ≥1 flare per year¶:

Work Productivity Loss# (In Those Aged <65 Years)

Patients with any loss**

78%

n=42

days lost

per year††

Impaired Social Activities

Patients with any loss**

54%

n=65

days lost

per year††

Impaired Self-care Activities

Patients with any loss**

52%

n=65

days lost

per year††

¶A 1-year prospective, observational study was conducted among patients with symptomatic disease in the US in 2001 (N=110). Inclusion criteria required patients (1) aged ≥18 years, (2) to have documented, crystal-proven gout, (3) to have symptomatic gout, and (4) to be intolerant or unresponsive to conventional therapy (sUA ≥6.0 mg/dL).16

#The study did not specifically collect employment information, so retirement age (65 years) was used as a proxy.16

**Data represents mean.16

††Data represents average overall, including patient with no days lost.16

Be the First to Know More

Be the first to know about our updates in uncontrolled gout.

References

1. Francis-Sedlak M, et al. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(1):183-197. 2. Morlock RJ, et al. Rheumatol Ther. 2025;12(1):37-51. 3. Dalbeth N, et al. Lancet. 2021;397(10287):1843-1855. 4. Timsans J, et al. J Clin Med. 2024;13(24):7616. 5. Elgafy H, et al. World J Orthop. 2016;7(11):766-775. 6. Dalbeth N, et al. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):69. 7. Ahmad MI, et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:649505. 8. Khanna P, et al. J Clin Med. 2020;9(10):3204. 9. Afzal M, et al. Gout. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; June 23, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546606/ 10. Keenan RT, et al. Am J Med. 2011;124(2):155-163. 11. Cipolletta E, et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023;75(9):1638-1647. 12. Cipolletta E, et al. JAMA. 2022;328(5):440-450. 13. Perez-Ruiz F, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):177-182. 14. Singh JA, et al. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50(3S):S11-S16. 15. Zuo T, et al. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):207. 16. Edwards NL, et al. J Med Econ. 2011;14(1):10-15.